You have traveled the world multiple times as a photographer. What moment or image has left the most lasting impression on you?

Imola 1994, without a doubt.

“It was a cursed Grand Prix, Imola in 1994. A death during practice. Ayrton Senna didn’t want to start the race but was convinced to go ahead.” On the eighth lap, tragedy struck. After the start, the photographers walked up the track and arrived at the site of the crash that had just happened.

“We immediately understood he was dead. We took photos, but no one ever published them out of respect for this great driver.”

A total shock. An icon had just disappeared… he became a myth for the entire world.

In 2008, I was tired, and Formula 1 was changing. It was time to think about new adventures.

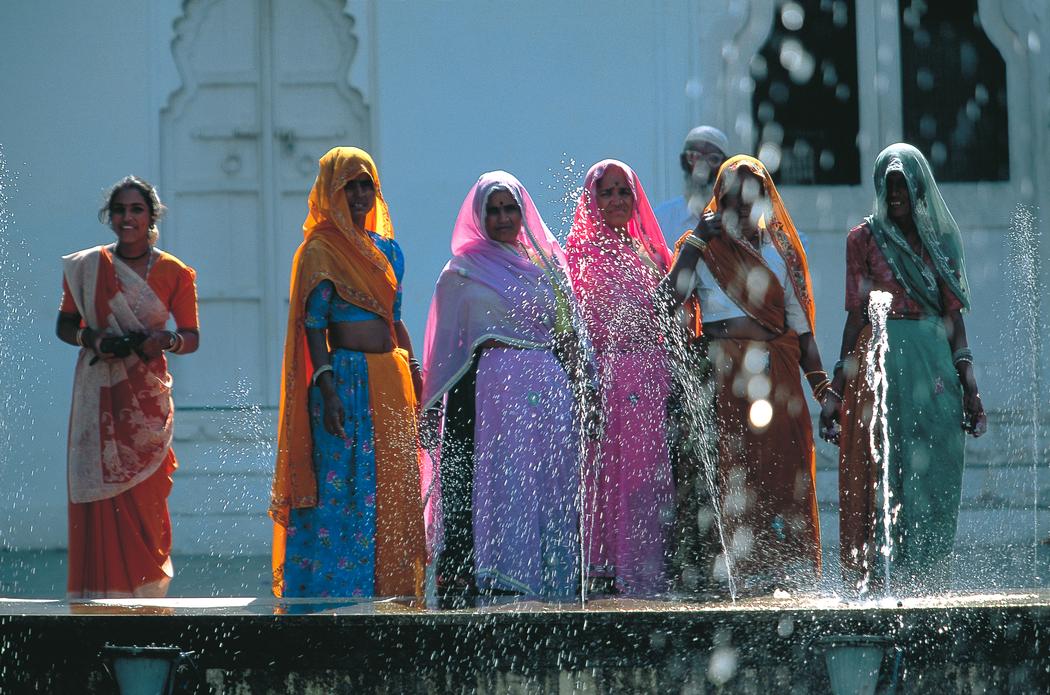

The discovery of India — a country of smells, colors, rituals, customs, and a thousand flavors… Incredible. I made two books and a documentary film.

How did your early fascination with Tintin and your grandparents’ influence shape your photographic vision?

Since the age of seven, I’ve been passionate about photography thanks to my two grandparents, who were enthusiastic amateurs, and to Hergé’s Tintin, which gave me a love for travel.

My desires quickly became incompatible with sitting in school — I left after two failed attempts at passing the science baccalaureate, with no chance of succeeding.

I briefly gave in and enrolled in a school for physiotherapy. But I’m stubborn. I sabotaged that path and decided to leave just a month before graduation.

What I really wanted was to be a wandering reporter, like Tintin.

Everything became clear: I would combine my two passions and become a motorsport photographer.

It was a big challenge — this profession is a closed circle that’s hard to break into, and living in Nîmes in the provinces didn’t help. But I didn’t care.

From Formula 1 to tribal communities, your subjects are incredibly diverse. How do you choose what to photograph?

I dreamed of immersing myself in the tribal world. I decided to set off for new horizons… ethno-photography.

Tribes in the Amazon, India, Africa… I made several books and then moved on to camera work and documentary filmmaking.

A new opportunity arose: I was invited to India to film with Dominique Lapierre, the bestselling author who had become a philanthropist there.

We decided to shoot a feature-length film about City of Joy, 25 years after the release of Lapierre and Collins’ bestseller of the same name.

The film is titled: “Spiritual India – In the Footsteps of the City of Joy.”

After that, I found myself in Africa, meeting some of the most primitive tribes on the planet.

I continued all the way to Tierra del Fuego and even met the last shamans of North America and the Amazon.

In France too, I found a new field of exploration by filming a feature about unusual carnivals, revealing strange little tribes across the country.

What drew you to the theme of rust, and how does it connect to your abstract work today?

Unusual compositions, bringing together objects and materials overlooked by today’s eye — most of them once used in everyday life.

Why rust, you ask?

Erosion — the process of degradation and transformation caused by external elements (temperature, seawater or rain, acidity) — gives a new life to these abandoned objects and brings them new colors and forms.

Rusty nails, old metal plates, abandoned gates, old pipes, shredded car bodies — they evolve every day, just like the impermanence of life.

Have you heard of “pareidolia”?

It’s when an image makes you see something else entirely, and reveals another world. You imagine shapes resembling animals, human figures, objects… giving the photo a completely different meaning.

This will be the subject of my next book. Fascinating.

You’ve mentioned never publishing photos from Ayrton Senna’s tragic crash out of respect. What role does ethics play in your work?

A very important role. We live in a surreal world — barbarity, killings, war, lies, racism… horrifying.

Ethics, in that context, is a form of respect.

How did your transition from photography to film enrich your storytelling approach?

I’ve been telling myself stories since I was little (though I haven’t grown much since).

I don’t really plan. I observe, I meditate — which leads me to contemplation, reflection, imagination, and daily creation.

The world is a wonderful playground, and life is a continuous string of adventures.

Can you describe your creative process when working with rusted metal in painting and sculpture?

Art must stimulate the imagination.

As Rudyard Kipling said:

“All things considered, there are two kinds of men in the world: those who stay home and the others.”

Without hesitation, I belong to the second category.

0 comments on “Dominique Leroy”